We’re So Cool: The Professional Critics v. Bikini Kill

Last month, Bikini Kill released the 20th-anniversary edition of their self-titled debut EP on their new eponymous label.

Dischord Records commemorated the occasion on its website; Ian MacKaye produced the record and was an early fan of the band. Coincidentally, in a Nov. 20 interview with The A.V. Club‘s Marah Eakin, Kathleen Hanna compared herself to a “female Ian MacKaye, but with fewer morals. Spin ran an entertaining oral history of the band’s first years. (Best part: Justin Trosper of Unwound’s anecdote about flunking high-school English after bringing Kathleen Hanna to speak to his class.)

All the requisite fanfare for a big-deal reissue, in other words. And as far as rock music goes, Bikini Kill is undoubtedly an important record. It provided inspiration to thousands of listeners; it rightly made a lot of detractors very uncomfortable, particularly in hardcore. Even in the late 1990s, an era hardcore fans remember for political correctness—in both the Old Left and Fox News senses of the term—run amok, columnists admitted or confessed to liking Bikini Kill in such right-on zines as HeartattaCk and Maximumrocknroll. It ushered in new discussions about gender politics, sexism, and sexuality in rock—punk and “alternative rock especially, which so often believed themselves to be beyond criticism in that regard. It was confrontational. It was direct. In a very real sense, it had not been done before.

Yes, truly a groundbreaking release. What gets overlooked, though, in Bikini Kill‘s historical significance, is the music itself. And let’s be real: the music isn’t there yet.

Now, I like Bikini Kill—a lot, actually. From “New Radio on, the band produced one of the 1990s’ finest bodies of work. Sadly ignored in the media frenzy surrounding riot grrrl and “women in rock was the fact that Bikini Kill could write a damned catchy tune when they set out to. Their later material, in particular, exhibited a heavy mod influence—shades of the Jam and the early Who are all over their best (and final) album, 1996’s Reject All American. But in 1992, Bikini Kill sounded sloppy, abrasive, largely devoid of nuance. Perhaps that was the point—on “Thurston Hearts the Who, Bratmobile’s Molly Neuman reads a Thurston Moore-penned review of their live performance that dismissed them as agitprop, political ranting behind the pretense of musicality. (Moore later publicly supported the band, while Hanna appeared in the video for Sonic Youth’s “Bull in the Heather.)

I dislike their first record for the same reason most hardcore of any era sails over my head at this point: unbridled fury becomes monotonous after a couple of moments. Not everyone agrees, of course—most of the zine writers who named Bikini Kill as a guilty pleasure could write 5,000 words praising Finnish thrash outfits that sound like a bus overheating. But me? Give me dynamics—that’s my personal preference. Give me growth. Give me the band’s difficult third album.

But most professional critics didn’t see it that way. To them, Bikini Kill’s primal rage represented the band’s apex, not its tentative first steps into the world. In his capsule biography of the band for Trouser Press—the self-proclaimed “‘bible’ of alternative rock since 1983; Pitchfork for the pre-Pitchfork age—Thomas Wolk cited their later work for diminishing returns (Reject All American especially) while gushing over the “ardor of their earliest attempts. Allmusic took a similar tack: as Stewart Mason praised Bikini Kill as their “purest expression, Stephen Thomas Erlewine dismissed Reject as an exercise in “preaching to a converted audience that was “sort of irrelevant. Their ire had subsided; their work, as it matured, failed to capture the white heat of their first batch of songs.

Well, of course it did: Reject All American was the product of a band six years older than the one that wrote that initial EP. Six years age an artist, or at least should. For Bikini Kill’s last album to retread the naked anger of their first would be dishonest. Their lyrics evolved from slogans to introspection, from the overtly political to something more personal, from the direct to the impressionistic. Likewise, their music grew from squalling noise to include melodies and moods. Artists can only run on “immediacy (Erlewine again) for so long before they look to other sources of inspiration in the world outside and the world within.

(Aside: I know quite a few women for whom Reject All American was their introduction to Bikini Kill, and who have named it as an eye-opening moment in their lives. Who, exactly, are the converted? The critics themselves? Good lord, did they actually read the liner notes? Would “the Sylvia Plath story be immediate enough for them?)

Of course, I am not among Bikini Kill’s target audience. I’m male, writing about a band that was by, of, and for young women. I’ve never had to deal with the issues riot grrrl addresses—certainly not in any direct fashion—and I’m not about to claim them for my own. To do so would be false and insulting. So on some level, perhaps I simply can’t identify with the band’s earliest songs and therefore can’t make the leap between what I hear coming from the speakers to what’s written on the lyric sheet. I have seen several bands of young women cover early Bikini Kill songs (and one all-male band that played “Rebel Girl, which was… odd). I’ve never heard any play “I Like Fucking, say, or “Bloody Ice Cream.

Perhaps I never will; perhaps, too, I’m not meant to.

Part of Bikini Kill‘s power lies in its proud lack of universal appeal—especially when “universal usually defaults to white-straight-male anyway. If anything, though, that makes the professional affection for Bikini Kill all the more perplexing. Thurston Moore’s early appraisal of the band may have been brutal, but at least it seemed honest. What, then, of Trouser Press and other publications that demand at least some semblance of musicianship from the acts they champion?

Anger is an easy emotion to co-opt. It’s surprisingly difficult to convey a political message through art, despite the fact that artists try it all the time. Prioritize art, move towards abstraction, concentrate on aesthetics, and you could lose your rhetorical focus; prioritize politics, remain direct and on-message, and you risk becoming a symbol, a badge of honor for outsiders who “get it. Champion Bikini Kill for their politics, write a few hundred kind words about how down you are with their cause, and you’ve absolved yourself for your support of sexist artists or refusal to challenge rockism or what-have-you. That seems to be the sensitive-new-age-guy critic’s thought process, anyway—the snide, patronizing “I’m a feminist, darling type, or the shy fragile creep. They didn’t love Bikini Kill’s ideas; they loved the idea of Bikini Kill. (“Hamster Baby on 1993’s Pussy Whipped took on U.K. critic Everett True for being exactly this kind of colonizer hanger-on.) They praised not their art, but their authenticity.

This isn’t to say that every male critic who praised Bikini Kill did so out of a sense of obligation or to score brownie points. Robert Christgau, longtime music editor for the Village Voice and MSN blogger, praised Bikini Kill for its ideas, the same as the other righteous dudes I’ve mentioned. But he also pointed out “the way Kathleen Hanna slips into the Cockney ‘roights’ on ‘Double Dare Ya’ and concluded, “Polly Styrene discovers ideology. Ideology discovers Poly Styrene. In other words, he actually discussed what the damned thing sounds like. (And while comparing female-fronted bands to each other is a common lazy critic’s cop-out, Christgau is right: early Bikini Kill did sound more than a little like a rickety X-Ray Spex.) Notably, too, he is the only professional I could find who appreciated the band as it evolved. From his review of Reject All American: “The first album got over on spirit. Here Kathleen Hanna’s vocals and Bill Karren’s guitar add definition, confidence, (let’s bit the bullet and call it) technical skill. Also, right, tunes. Not a word from Christgau about the band spinning their wheels as their sonic palette gained a few new colors.

Now, granted, one could accuse Christgau of also falling into the I’m-so-cool trap. I single him out for two reasons—well, three, actually. The first is practical: his work is widely read, widely cited, and, among rock writers, hugely influential. The second is his overall approach: Christgau has always placed his politics up front and has consistently evaluated music based upon its social content. Where most reviewers praised Guns N’ Roses’ Appetite for Destruction upon its release in 1987, for example, he quickly pointed out Axl Rose’s thorough disdain for women in his lyrics. Whether that is a valid reason to trash the album (as Christgau did) is a matter of personal perspective, but the man is not a bandwagon-hopper.

The third, and most important, reason: Christgau recognizes Bikini Kill as artists. Not ideologues, not theoreticians—when they step into a recording studio, they’re musicians. So he reviews their music. Simple as that.

Music can galvanize people into action, open them to perspectives they’d never before considered, free the lonely from isolation. But music is also art, and it should be evaluated as such. It insults the artist to pretend that a work should be judged by function over form. And, aside from Christgau, none of the reviewers I mention ever answers the central question: “Do I like this? They avoid it at all costs, in fact, shrouding their evasion in talk of rawness and passion. (Wolk goes one step further, calling the band’s politics “suspect before quickly stepping back to effusiveness. Candor without honesty.)

Part of this stems from reviewers having short attention spans; few have the patience to watch a band grow. Part of it comes down to the way pop music intersects with politics. Most political bands suffer from some version of this at some point in their careers. As the Clash’s music and lyrics became more experimental and abstract on Sandinista! and Combat Rock, out came the cries of sellout! not punk! rock stars!, as if they hadn’t been huge to begin with. Crass took the opposite tack: they grew ever more blunt, with lyrics in perpetual attack mode and music that ditched all attempts at melody or structure, in an attempt to shake loose an audience of sycophants, to spur them into action instead of spouting copycat politics that grew more diluted with each passing year. In the end, dejected, they realized that there was just no way to do so.

If even one of those critics said that he actually liked Bikini Kill—if one of them actually mentioned how they sounded—I wouldn’t doubt him. Disagree, maybe, but not doubt. Music, like any art form, is subjective; every song, every band, is someone’s favorite. But they can’t bring themselves to do that: to admit that they don’t like it. Or worse, that they don’t get it. Worse yet: to admit that they don’t care. No, the reader instead has to parse that out from blocks of weasel words and dog whistles. All because critics felt the need to impress a band and a movement that from the outset sought to define themselves outside of their gaze, instead of doing their jobs as journalists: honest reporting.

How winsome. How baldfaced. How… high-school. The dudes want a shot at the untouchable too-cool girl for a date to the prom. Given all their fawning, it’s not hard to read their repudiation of Bikini Kill’s later work as the result of that too-cool girl spurning their advances time and time again. Hell, they never really cared about her anyway.

But perhaps I’m getting way, way ahead of myself. Switching gears: I’ll admit that Reject All American suffers from a couple of duds—notably “R.I.P., a tribute to a friend of Hanna’s who died from AIDS. Stuck at the end of the a-side, sandwiched between upbeat mod-rockers, it sounds morose and awkward; the only reason I listen to it is that I rarely want to get up to move the tone arm when the record’s about to run out anyway. The intent is admirable, the meaning touching; the actual song… not so much.

But—and this is the crucial distinction—I like that it’s on there at all. By the end of their recording career, Bikini Kill had moved beyond shrieks of rage and one-two punches at specific targets. Their lyrics and approach had… not mellowed, exactly… expanded to embrace a broader range of emotions, ones that are harder to put into words: personal frustration (“No Backrub) and loss (“R.I.P., “For Only, “Tony Randall—a theme of loss pervades the album, actually). For the most part, their final songs lack the celebratory call-to-arms quality of their earliest anthems. But that gut-punch quality is replaced by a new maturity, a personal intimacy that says more about Hanna, bassist Kathi Wilcox, and drummer Tobi Vail as writers and people. But while the personal is political—I took that as the thrust of Bikini Kill’s whole approach—it’s also much harder to reduce to a slightly thornier version of Girl Power.

In other words, it got harder to earn points for liking Bikini Kill once they started acting more like a band and less like a cultural phenomenon. So for male rock critics latching onto to them for street cred, what was the point? Maybe if Bikini Kill hadn’t dissolved shortly after Reject‘s release—maybe if they had released a fourth or fifth or tenth album—they would have viewed it as a new phase instead of an abandonment of purpose. As it happened, they couldn’t appreciate the band’s art for itself rather than as a symbol.

No matter, I suppose. The fact remains that I’m an outsider to riot grrrl and to Bikini Kill, and one who ultimately enjoys them for their sound. Neither entity is, or should be, impervious to critique, and there’s plenty to critique about both—but that’s not what I’ve set out to do here. At the end of the day, riot grrrl was a subculture with its own rules for inclusion and exclusion just like any other, and Bikini Kill was simply its best-known representative. And, like any product of subculture that outsiders try to adopt for their own, most lost interest when they grew past its original codes and manifestos, when the band lost its underground cachet amid glowing coverage in mainstream entertainment rags and teen magazines. (I seem to recall some pretty positive, if misapprehensive, write-ups of riot grrrl in my sisters’ copies of Seventeen circa 1995. Recoil, Trouser Press, recoil.)

In any event, it’s nice to see that current reviews of the reissued Bikini Kill (Pitchfork‘s, for example) are largely written by people who genuinely like the band for its music as well as for what it signifies. Two decades of perspective? Perhaps—or perhaps it’s simply good journalism. (Good journalism and Pitchfork in the same paragraph? It’s true. Will wonders never cease?)

And good for them. Bikini Kill may not be for me, but I’m glad it’s out there again for others to discover (or rediscover, as the case may be). Usually I’m not a fan of reissues, but for my part, I await the day when Bikini Kill gets to its later catalog. Hopefully those releases will feature the same attention to presentation, with liner notes and photographs that tell the story of how the band evolved—of how their abilities developed to match their ambition. Because isn’t the process the real point of art?

Yeah, I think so.

My grateful acknowledgement to Gabrielle Moss, who happily let me bounce some ideas off of her as I drafted this piece.

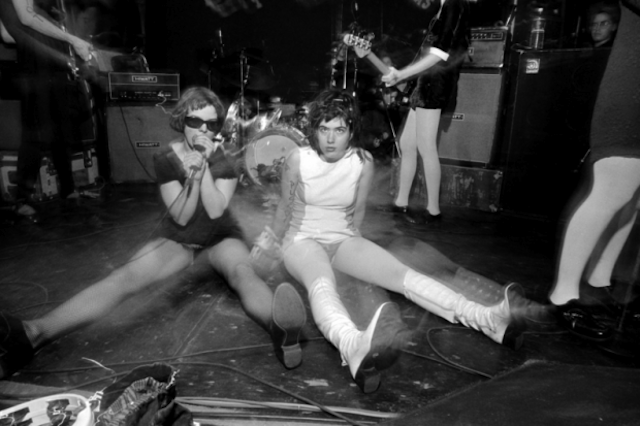

Featured photo by Pat Graham