Review: Magazine, No Thyself

Could Magazine have been the biggest band in the world? Not a chance. Next question: did they want to?

When lead singer and founder Howard Devoto quit the band in 1981, he cited low album sales as the reason for his departure. Devoto was twenty-nine then, by which age he should have either succeeded in music or surrendered to the workforce. (In his native Britain, where teenagers regularly started full-time careers, he probably should have given up five or six years earlier.) Magazine did not fail, exactly, but they defined the term “cult band: beloved by a small clutch of critics, despised by just as many, small but devoted fanbase, ignored by the larger public.

Magazine presented themselves as a connoisseur’s band; also, as pricks. They knew full well that they were smart musicians, a fact they never failed to advertise. They positioned themselves at the avant-garde, relying upon futuristic keyboards and scathing lyrical introspection where pub rock and punk demanded back-to-basics anthems. Across five albums – four studio, one live – and a handful of singles, Magazine exuded the barely-suppressed fury of over-educated twenty-somethings bashing up against the realization that the world is not, in fact, a meritocracy. They longed for mass appreciation, yet reveled in a style that was, for most listeners, nearly impossible to appreciate.

And they baited critics. Devoto quit the Buzzcocks and declared punk a spent force in the spring of 1977, a ploy for attention from a British music press whose obsession with that scene had not yet reached full force. Magazine’s learned aesthetic either drew praise from reviewers – Rolling Stone declared their debut single “Shot by Both Sides “the best rock & roll record of 1978, punk or otherwise; of their first album, Melody Maker‘s Chris Brazier gushed, “No one that has the slightest interest in the present and future of rock ‘n’ roll should rest until they’ve heard Real Life – or drew flak. Robert Christgau in 1979 called Magazine “the most overrated band in new wave Britain and dismissed their “published-poet lyrics as “pretentious. (Not content to rip them once, a few years later Christgau denounced Devoto as “the definitive art-twit: “We hate you you little smarty.)

Not that they weren’t influential – their influence just remained below the surface, more attitude than sound. They wrote the theory; others picked up the text and put it into practice. Members continued on to greater success with Siouxise and the Banshees, Public Image Ltd., and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds. The Magazine-Ultravox side project Visage resuscitated the latter band’s career; without Magazine, we might not have the hit “Vienna. Morrissey swiped his self-loathing persona and his swooning vocal delivery from Devoto; in 2006, he covered their single “A Song From Under the Floorboards as a b-side. Corey Rusk and Tesco Vee named their hardcore-turned-indie label Touch and Go for the band’s second single. Surely, too, Magazine’s exploration of the brutality of human relationships rubbed off upon professional gadfly-guitarist-producer Steve Albini.

But when music journalists proclaimed a post-punk revival last decade, they meant bands that copied Joy Division or Gang of Four; no bands rushed up to fill a Magazine-shaped void. (Notably, despite the group’s critical stature as a post-punk pioneer, Penguin omitted the chapter about Magazine from the U.S. edition of Simon Reynolds’s post-punk primer Rip It Up and Start Again.) Magazine did well enough in their day, both here and in Britain, but they weren’t household names – simply moderately successful musicians, making enough to sustain their career for one more LP, one more single, one more tour. Their 2009 reunion – minus original guitarist John McGeoch, who died in 2004 – was appropriately low-profile: a U.K. tour, a few one-off shows. Eventually, Magazine’s renewed activity led to a new album: No Thyself, released last fall on U.K. indie Wire-Sound.

It’s not Magazine’s finest work. Devoto commits a couple of uncharacteristic lyrical fumbles. The pornographic “Other Thematic Material comes off as clumsy when it should be raw and blunt. (Not offensive, mind – I’m an adult, so sex does not offend me – just gross.) Devoto’s best writing centers on his own flaws and anxieties; empathy is not his strong suit, leading to the well-meant but flat Joy Division tribute “Hello Mr. Curtis (With Apologies), which also eulogizes Kurt Cobain. In spots, too, the complex music stiffens up where their earlier, equally deliberate material flowed. It becomes too dense, too remote even for a band that made its name pushing out to rock’s frontiers.

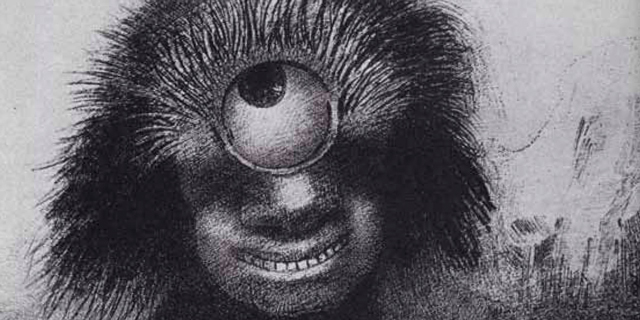

But if No Thyself rates as slightly subpar, that’s only because they set the bar so high to begin with. If anything, its moments of awkwardness reveal the components that make the band work. Flailing for words to describe Magazine, reviewers often settle for calling them art rock, and they’re right – Magazine are surrealists. They twist the familiar into something alien; at their best, they force clashing elements into a seamless, otherworldly whole. Sixties Stax organ parts remade with Seventies sci-fi synth sounds live beside jazz fusion basslines and driving rock drumming. Bassist Barry Adamson, who fans argued was their true x-factor, initially participated in the reunion before opting out in favor of his day job composing film scores. Yet one would need to check the liner notes to confirm his absence. Replacement Jon “Stan White draws heavily on Adamson’s style but does not stick out as a mere mimic; rather, his playing continues where his predecessor left off.

Keyboards have always formed the basis of Magazine’s sound. Guitarist Noko, who collaborated with Devoto in the singer’s late-Eighties project Luxuria, lends a tasteful shoegaze character to Magazine’s sound without transforming or overwhelming it; his Stooges-meets-Slowdive guitar mostly adds texture and accents, with the occasional solo or lead break. (Noko does take a few well-earned moments in the spotlight, particularly on opening track “Do the Meaning.) They use the basic components of rock music, then flip the proportions and alter the tones, jarring the listener’s expectations of how the genre works. On top of it all: Devoto’s sneering, over-enunciated vocals, singing songs of frustration, of bitterness, of resignation. His gasp ties the whole thing together, contributing a final layer of analysis to their difficult but well-mapped music.

Surrealism was a highly theoretical movement; its members penned manifestos detailing the direction in which they hoped to push art. Each Magazine album similarly serves as an outline of their philosophy, a synthesis of their knowledge. The new incarnation of Magazine hasn’t altered its approach; Wire-Sound fits them perfectly, the musical equivalent of a specialized small press dedicated to publishing only the finest examples of its editors’ tastes. No Thyself is comfortable within its niche in a way that their original-period albums on Virgin weren’t. Like I’ve said, this isn’t Magazine’s best album – that’s a pick-’em between 1979’s bleak Secondhand Daylight and its poppier 1980 follow-up The Correct Use of Soap. But the best artists and the best thinkers possess an encompassing world view, and even their lesser work expands upon that vision. Kurt Vonnegut felt that Slapstick was the worst novel he ever wrote, yet its sloppiness laid bare his philosophy of life more thoroughly than many of his more celebrated books. Likewise, while No Thyself feels less like a new chapter of Magazine’s career than an epilogue, it enhances one’s understanding of a band that set out from the start to build a canon. And to understand Magazine is to love them.

Who are Magazine’s fans? The band initially sprang from a brief moment when the British popular music press treated bands like academics and records like thesis statements. Young people flocked to universities and art schools (better a useless education than pissing away one’s life in one of the U.K.’s increasingly scarce industrial jobs) to load their minds with emerging theories of culture in the postmodern world. They bought records, including Magazine’s. But the band always stood somewhat aloof from their college-aged audience – a little older and a little more cynical about life. I picture the ideal Magazine listener being much like myself when I first heard them: late twenties, with an overpriced history degree; playing in a band while jockeying the information desk at Barnes and Noble; agonizing over the value of pursuing my own interests when there clearly wasn’t any money or glamour in it. Not exactly the lifestyle people write hit songs about.

Overthinkers, however, need anthems too; for that reason, Magazine spoke to me. They didn’t reassure me that life would turn out okay – music by and for adults doesn’t, and probably shouldn’t, do that. But they did show me that one can make good music – relatable music; challenging music; intelligent music – out of unromantic circumstances. Howard Devoto was twenty-six when Real Life came out. Today, he’s sixty. For the past twenty years, he’s worked as an archivist, writing music as an occasional project. Yet his band just created an album that stands confidently with those that came before it – imperfect (as are all things), but fully worthy. More than anything, No Thyself proves that one can accept the ugliness of adult life without collapsing under it; that responsibility and failure and frustration can inspire creation rather than stomp it out.

Best professor I’ve ever had.

No Thyself was released October 24, 2011. Available on LP and CD from Wire-Sound (www.wire-sound.com).